You have an idea or observed a problem. But you’re smart enough to not jump right into building a product. How do you get enough validation to know if you should continue or not?

Every startup is different, but also the same. That’s because they (should) all start with this one crucial step.

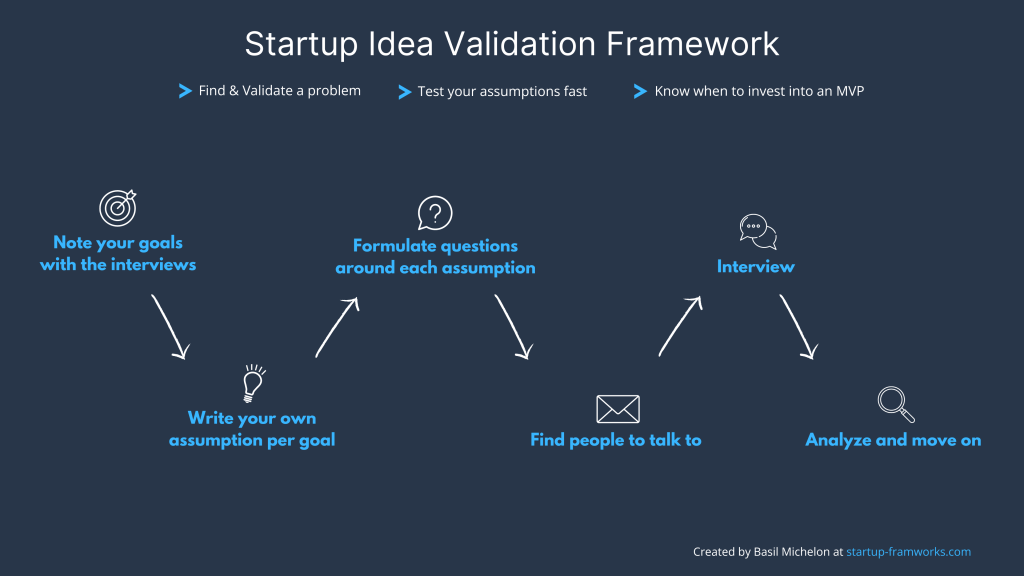

Validating your idea starts with comparing your assumptions to the real world. It’s the first and one of the most important steps along your startup journey.

Actually, it is the second step. If you have an idea or observe a problem, start with an online search. Try to find out more about the problem, look for existing solutions, and consider whether there is a big enough market for the idea.

But if you are still convinced that you are on to something, it is time to test your assumptions in the real world.

There are three commonly suggested ways to run your first validation:

- Talking to people and learning about their problems

- Building a landing page and get people to do some call-to-action

- Trying to pre-sell your idea

This framework only includes the first point, which is what the majority of founders should focus on.

Trying to pre-sell a non-existing product will be almost impossible if you are not an absolute sales-god or don’t have an existing audience. When was the last time you paid for something that didn’t exist?

On the other hand, landing pages can be valuable tools on your path to validation. But website traffic or email signups won’t say much about what people really think.

You should only use them in combination with real conversations or if you already have a good understanding of the problem and target group.

With this framework, you have a practical guide on how to validate your initial assumptions cheaply and quickly. It is based on the experiences of many successful entrepreneurs, such as Jason Cohen, Mitchell Harper, and Rob Fitzpatrick. All primary sources are at the end of the page.

Note your goals with the interviews

Before formulating questions and reaching out to people, you have to be clear about what you want to learn.

- Who is your ideal customer (ICP)?

- What problems do they have?

- Do they experience a specific problem, and how?

- How urgent are those problems?

- How did they cope with the problems in the past?

- If you target businesses: Is there a budget to solve these problems?

Put your goals into the first table column of your note app or a spreadsheet. This will help you write down your assumptions and interview questions in the next steps.

You might have noticed that the list does not include any goal related to your solution (or rather, your idea of a solution). That’s because you won’t learn anything by asking about your ideas.

People won’t tell you that your idea sucks. They will be nice and give you a lot of “this could be interesting” or “I might pay for that.” But these hypotheticals tell you nothing about what they really think.

So, put yourself into exploration mode and avoid trying to sell your idea.

Write your own assumptions per goal

Having your goals laid out, you now want to add your own answers in the second column of your table. Or rather, you want to add what you assume the answer is.

This is crucial. You need to be conscious of the assumptions in your head. Those assumptions will guide your decisions about everything from product to business model.

By writing them down, you’re less likely to fall for confirmation bias during your interviews, and it will allow you to test your assumptions more systematically.

Let’s look at an example from PayZlip, my first SaaS startup. We started PayZlip because payroll for small Swedish companies was over-complicated and usually outsourced to external consultants.

One of the goals we set to test was to:

“Understand how small company owners think about and work with salary costs.”

Our initial assumption (answer) was that:

“Small company owners would like to control their salary costs directly and not have to rely on their external consultants.”

Formulate questions around each assumption

With one or multiple assumptions per goal, you now have a great starting point to formulate interview questions.

This is harder than the previous steps, and there are some pitfalls that you need to avoid. Asking the wrong questions can destroy any helpful learning. Or even worse, it can mislead you into following the wrong assumptions.

Here is what you SHOULD do when formulating questions:

- Ask open-ended questions

- Ask questions about the topics of your assumptions, not about your assumption

- Ask about actual things that happened in the past, not speculations about the future

To emphasize these points, here is what you SHOULD NOT do:

- Don’t ask any questions about your solution

- Don’t ask questions that can be answered with a “yes” or “no”

- Don’t ask any hypotheticals like “Would you” or “Could you”

- Don’t try to wing their answers (“I think this, what do you think?”)

Returning to the PayZlip example, let’s look at a bad and good way of formulating questions based on the assumption that:

“Small company owners would like to directly control their salary costs and not rely on their external consultants.”

The wrong way to validate the assumption is to ask a question like:

“You have an external accountant. Would you prefer to be more independent and control more data, like salary cost, without relying on them?”

So, don’t ask directly about your written assumption. Instead, ask open-ended questions about the topic of your assumption:

“Do you ever think about your coming salary costs? When do you think about them? How do you think about them? If so, are you doing something to act on it? Do you have an example of when that happened?”

Note your questions in the third column, next to the corresponding assumption.

Find people to talk to

Founders struggle with this the most. It’s not the hardest part, but it takes the most time and demands persistence.

Start by defining your ideal customer profile (ICP). Those are the people you assume to be most affected by the problem. Of course, it’s only an assumption at this point.

You should be as precise as possible, but define at least:

- The industry they work in

- The company size (employees or revenue)

- The job title

- If it matters, the geographical location

Or if you target consumers, focus more on:

- Demographics

- Sociographic

Next, find out through what channels you can reach your ICP.

Are they active on LinkedIn? Do they often check their email? Is there any physical location where you can catch them? Or would an ad on Craigslist do the job?

Avoid only talking to people you already know. They can be a good source to bounce around ideas before you start your validation process, but they are biased towards making you feel good.

Your message when reaching out should be short and to the point. Remember, you are not trying to sell. You are on a discovery journey and trying to understand what parts of their lives are annoying.

You might want to add more detail, but you can form your message around:

“Hi (name),

I hope to talk to (ICP) experiencing (problem). I have nothing to sell, but I am doing research to work on a possible solution.

Would you have 15 minutes for a short call?”

If you have some money, you can even offer to compensate them for their time. Most people will not accept your money after talking to you anyway.

Interview

Take notes in the fourth column next to your questions during the interview.

Even if you created a nice structure in the previous steps, allow the conversation to take unexpected turns in new directions. If you make it an interrogation, you might miss out on the sweet “wait, that’s interesting” moments.

Analyze and move on

So how do you know when you are done?

The truth is that you will never feel fully convinced that you are right about all of your assumptions. And that’s okay. Your conversations are only the first step in a much longer validation process that only ends when you find product and business market fit.

You should stop your interviews when you feel like you are not learning anything new and when you feel secure enough to start spending time and money on an MVP.

Sources

- The Iterative-Hypothesis customer development method – by Jason Cohen

- How to Test & Validate Your Startup Idea or Product Without Spending a Single Dollar – by Mitchell Harper

- Lean Market Validation: 10 Ways to Rapidly Test Your Startup Idea – by Jim Semick

- Use This proven Formula to Validate Your Next Startup Idea – by Rob Walling

- 12 Tips for Early Customer Development Interviews (Revision 3) – by Giff Constable

- 11 Customer Development Anti-Patterns – by Giff Constable

- Should you sell a product before building it? – by Tyler King

- The Mom Test – Summary and Insights – by Rob Fitzpatrick